Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

Signed in as:

filler@godaddy.com

APRIL 2014. By JANEL ST. JOHN

Frederick Douglass fought slavery with the force of his voice. Ida B. Wells exposed the terror of lynching when the nation refused to look. Booker T. Washington built educational systems from the ground up; W.E.B. Du Bois challenged America with data, scholarship, and relentless advocacy; and Madam C.J. Walker transformed Black entrepreneurship into a platform for philanthropy and social uplift. These leaders lived in the trenches of America’s hardest battles - abolition, racial violence, voting rights, and economic survival. Yet even amid those urgent fights, they recognized another front in the struggle for equality: the right to define and celebrate Black beauty. They wrote about it, debated it, funded it, and modeled it in their own public images.

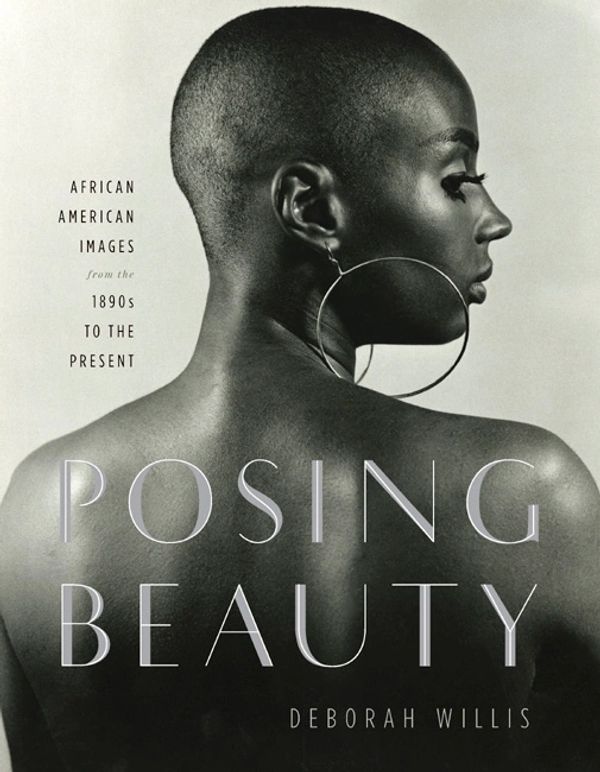

This is the lineage that Deborah Willis traces in her book and exhibition, Posing Beauty, African American Images from the 1890s to the Present. She points out that it was early African American leaders, photographers, newspaper editors and artists, who spearheaded the movement to showcase Black beauty in its proper context - devoid of the negative imagery often found in mainstream media, or simply omitted from it. It wasn’t until the late 1960s and early 1970s that Black models began to appear in magazines and newspapers. “Posing Beauty" is therefore, the first photographic history of Black beauty - a window and panoramic view of the life and times of African American people, as told or ‘constructed’ by her own people. It is a multifaceted story, so important, that leaders, time and again, created campaigns promoting Black beauty in visual culture. They understood of the power of an image.

In his own photos, Douglass often looked away from the camera, creating a profile ‘of intellect, of a scholar, of a free man in the 19th century.’ “When we look at these images of Frederick Douglas,” Willis said, “We see his style of dress. Style of dress and fashion was also important.” Her scholarship brought attention to another crucial moment in Black intellectual history. W.E.B Du Bois organized “The Exhibition of American Negroes,” a grand showcase of the accomplishment and progress of Black people and a direct challenge of racial stereotypes with images and objects. Du Bois installed 350 photographs of middle and upper-class Black life for display at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. Though generally ignored by mainstream American newspapers, the exhibit received over fifteen medals including two grand prizes and four gold medals during its time on display.

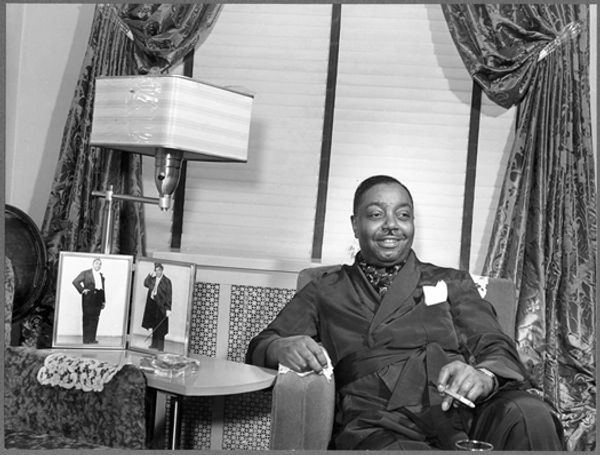

A Prosperous Chicagoan (Revery Clarence Cobb) Spending an Evening at Home, April 1941, Russell Lee

Mary Louise Harris on Mulford Street, Homewood, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, c. 1930-1939, Charles “Teenie” Harris.

Crowds Outside of a Fashionable Negro Church, Easter Sunday, Chicago, Bronzeville, April 1941, Edwin Rosskam

John W. Mosley (American, 1907–1969) Atlantic City, Four Women, c. 1960s, Gelatin sliver print, Courtesy of Charles L. Blockson, Afro American Collection, Temple University

But it was the image of a Runaway slave ad, that Willis said, significantly transformed her research for the book. The 1863 reward notice for a woman named ‘Dolly,’ was placed in an Augusta Police Station by Louis Manigault, owner of Dolly. The ad is very telling. It has a picture of Dolly and refers to her as being “30 years of age, light complexion, and rather good looking with a fine set of teeth.” It said that she had ‘never changed her owner, and had always been a house servant.’ “It is thought that she has been enticed off by some white man,” the ad reads. “Dolly was special to Louis,” Willis said. “She visited the photographer’s studio. She may have been a concubine.” The ad reveals a relationship as the owner expressed a sense of betrayal that Dolly may have left him for a white man. “In discussions of slavery, we rarely find a discussion that talked about beauty and women,” Willis said. “Women were seen as objects.” But this image clearly states Manigault’s desire for Dolly by describing her physical features. This expression of beauty is, in part, the basis of the exhibition based on the book, for which Willis also serves as curator.

“Posing Beauty in African American Culture” is now in view at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts through July 27, 2014. Photographers Carrie Mae Weems, Charles ‘Teenie’ Harris, Mickalene Thomas, Moneta Sleet and Gordon Parks, are featured among the 85 works of art. The show is an opportunity to peer into a world that many people never knew existed! With historical figures and celebrities, the exhibition is much more than beauty and fashion; “Posing Beauty” is a comprehensive ‘reading about Black life’ - from Easter Sunday to the neighborhood barbershop.

Ken Ramsay (Jamaican, 1935–2008) Susan Taylor, as Model, c. 1970s Gelatin silver print 26 1/2 x 20 in.

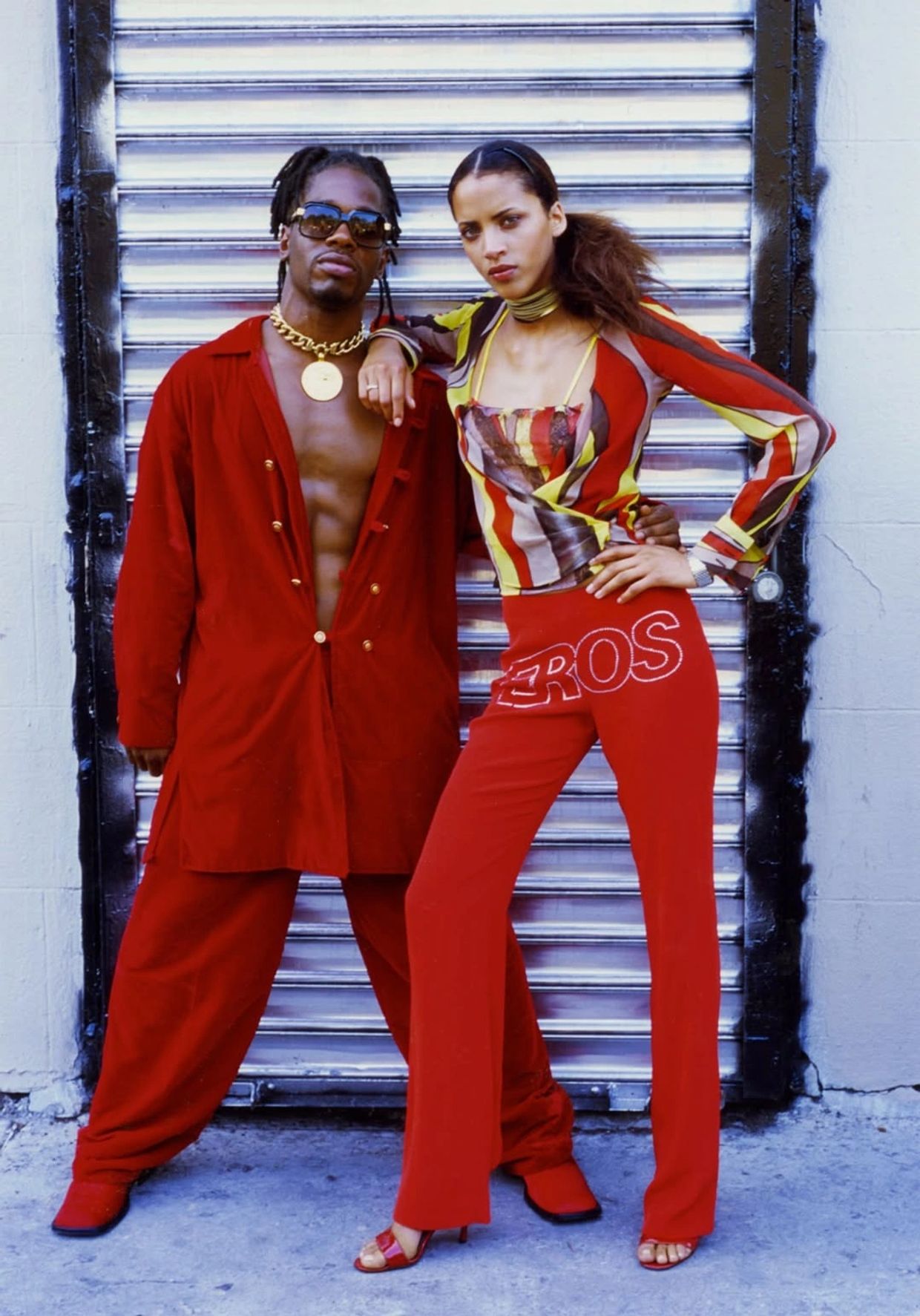

Jamel Shabazz, American, born 1960. Drama and Flava from Back in the Days, 2000. Color-coupler print. 29 1/2 x 19 1/2 inches.

Plastic Bodies, 2000, Sheila Pree Bright

Race, culture, identity and beauty are complex themes. But in the hands of brilliant artists, they are the basis of exceptional works of art. “Identity Shifts: Works from VMFA” is a thought-provoking series featuring 35 paintings, sculptures and photographs by African-American artists from the museum’s collection. It's now on view in conjunction with “Posing Beauty.”

Photographer Sheila Pree Bright’s, “Plastic Bodies” tackles all four themes at once. Bright said she was in grad school in 2000 when she developed the work. “I was a photographer in hip-hop culture when gangster rap was prominent,” she said. “And I became very aware of how a stereotype was ingrained. We project an image, but we’re not there to talk about it.”

Bright took the cultural icon of the Barbie doll to challenge the notions of beauty standards and highlight their imact on a young girl’s psyche. “I was looking at women of color and what we think is the ideal of beauty based in Western culture,” she said. “Women of color are really not happy with our physical looks and bodies. Actually, no woman can fit this body type without plastic surgery.”

Bright contends that blending of cultures is responsible for the desire of people to want to emulate each other. “We have become plastic and the Barbie doll has become human.”

Other photographers in “Identity Shifts” include James VanDerZee, Carrie Mae Weems and Hank Willis Thomas. There is also work by lesser known artist and Richmond native, Louis Draper who played a primary role in founding the first African American photography collective, Kamoinge, in New York in 1963.

Award-winning fine art photographer, Sheila Pree Bright is a “cultural anthropologist." Her work captures cultures and explores common intersections.

Get art + design news in your inbox!

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.